If you’ve been following my recent posts, I’ve been documenting some of the beautiful places we visited on this summer’s vacation, from Bryce to Zion to Grand Teton to Yellowstone. Not yet finished, we turned toward eastern Wyoming and South Dakota for the final leg of our journey.

East of Yellowstone, Wyoming has a classic rugged landscape, wild and rough, rocky and brush-covered, very much what I’d always envisioned.

While we were only passing through this area on our way from Yellowstone to South Dakota, the scenery was spectacular, weaving us past remarkable geological formations and gradually transitioning us from the tall peaks of the Rocky Mountains to the more open Great Plains. We kept to the driving plan, intending to reach South Dakota that very day, so we only paused now and again to take in the peaceful surroundings. We did stop briefly for lunch in Cody, Wyoming, and even ate at the Irma, the hotel and saloon made famous by Buffalo Bill. (As nice as that might sound, I’ll warn you that the food and service were quite a disappointment. At least the historic atmosphere was something to offer the boys.)

We kept to the driving plan, intending to reach South Dakota that very day, so we only paused now and again to take in the peaceful surroundings. We did stop briefly for lunch in Cody, Wyoming, and even ate at the Irma, the hotel and saloon made famous by Buffalo Bill. (As nice as that might sound, I’ll warn you that the food and service were quite a disappointment. At least the historic atmosphere was something to offer the boys.)

But South Dakota was the goal, home to the Black Hills and Mount Rushmore and the Badlands. We arrived in a most impressive lightning storm, which made our drive through the winding roads of the Black Hills most, uh, thrilling. Fortunately, by morning the skies were clear, and the storm had no lasting impact on our journey.

We camped near Custer State Park, so we started with a driving tour of the park to look for wildlife (okay, admittedly we slept in the car that night rather than set up our tent in the pouring rain at the campsite). A family of pronghorns greeted us a few miles in, but the most impressive numbers were of American Bison.

Custer State Park maintains a population of about 1,300 Bison.

Custer State Park maintains a population of about 1,300 Bison.

With such a large group, we saw bison of all ages.

There were many nursing calves with their mamas.

But it was also bison rut season. Many an older bull walked around with his intended mate, not leaving her side for a moment. Aside from literally pushing her around (I guess that’s where the term “bullying” originated?), the male would made deep guttural noises at the female, his tongue sticking out in the process. I was mesmerized by the bulls’ behavior, though I should point out that I find neither bullying nor tongues sticking out with simultaneous rumbling attractive in a man.

But watching a bison rut was fascinating. At one point a group charged forward, aiming right for my car. The best I could do was roll up my window and say a word of apology to my car in case it got gored, but they all passed on by. Aside from knowing that one of them was a big bull, I didn’t have a chance to notice the others in the group. I wasn’t sure whether the big bull was bossing females or giving chase to a foolish younger bull who strayed to close to the already-claimed girls, making them all run. It’s amazing how small a car can seem when these big herbivores are rushing toward you.

Even now I can look at these pictures and hear the deep grunts of the males.

This big male is wallowing in the dirt. While many bison will do this to when biting flies bother them or when they are molting, in rut season male bulls do this to both leave their scent and display their dominance.

This big male is wallowing in the dirt. While many bison will do this to when biting flies bother them or when they are molting, in rut season male bulls do this to both leave their scent and display their dominance.

Elsewhere at the state park, we saw wild donkeys, descendants of pack animals once used to reach the summit of Harney Peak, South Dakota’s highest point.

If visitors pay attention, they might also notice small mounds around. Prairie dogs!

These small rodents might be vilified by farmers and ranchers, but in the natural world they are an important keystone species. Their demise would result in the subsequent demise of many other species, some who depend on prairie dogs as prey and others who depend on the prairie dogs’ engineering role in the environment.

For example, prairie dogs are the primary food source for the endangered black-footed ferret, once thought to be extinct after prairie dog populations greatly declined, a result of habitat loss, extreme control methods, and disease. Burrowing Owls and Mountain Plovers build their nests in prairie dog burrows. Additionally, prairie dogs’ burrowing and grazing habitats improve soil quality, nutrient cycling, plant and animal diversity, soil water retention, and other ecosystem processes. Plus, prairie dogs kiss each other in greeting, and that’s just too cute.

For example, prairie dogs are the primary food source for the endangered black-footed ferret, once thought to be extinct after prairie dog populations greatly declined, a result of habitat loss, extreme control methods, and disease. Burrowing Owls and Mountain Plovers build their nests in prairie dog burrows. Additionally, prairie dogs’ burrowing and grazing habitats improve soil quality, nutrient cycling, plant and animal diversity, soil water retention, and other ecosystem processes. Plus, prairie dogs kiss each other in greeting, and that’s just too cute.

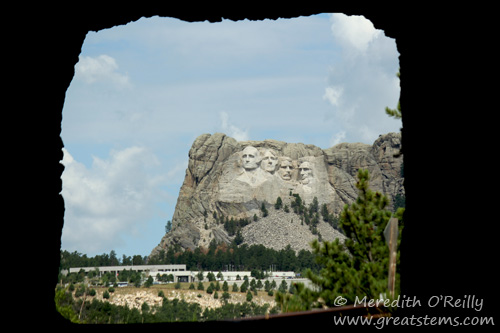

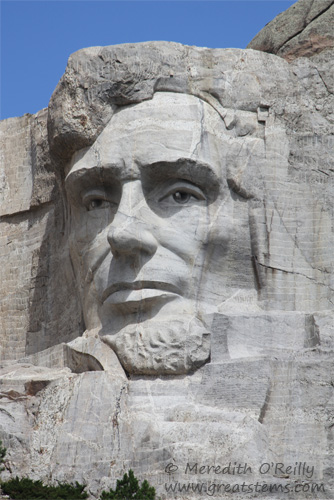

From Custer State Park, we headed back up to Mount Rushmore, which we had viewed for the first time during our nighttime drive in the treacherous storm of the night before. Up and down the switchback-heavy Iron Mountain we went, and short one-lane tunnels created occasional frames of the national monument. A new meaning to the phrase “tunnel vision”!

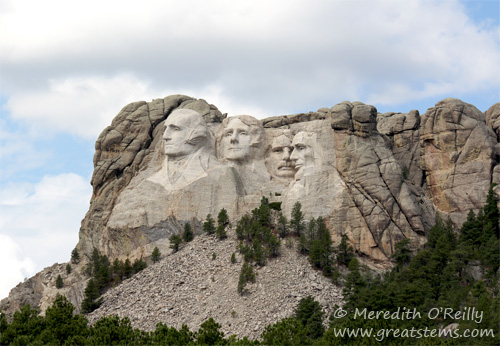

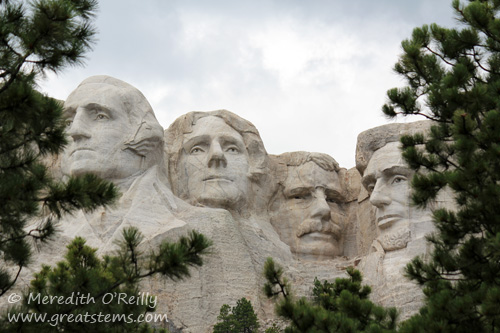

Mount Rushmore was the brainchild of South Dakota State Historian Doane Robinson and the grand masterpiece of artist Gutzom Borglum, who worked on the sculpture until his death in March 1941. I have mixed feelings about the monument, as I don’t like to see natural beauty marred and there is obvious controversy regarding the land being taken from the Lakota Sioux, but I acknowledge the power of the symbol for American patriotism and the phenomenal artistry and work of engineering that went into the giant carving.

The site was selected for its excellent granite and southeast facing, ideal for light. The surrounding Southern Black Hills is covered with Ponderosa Pines.

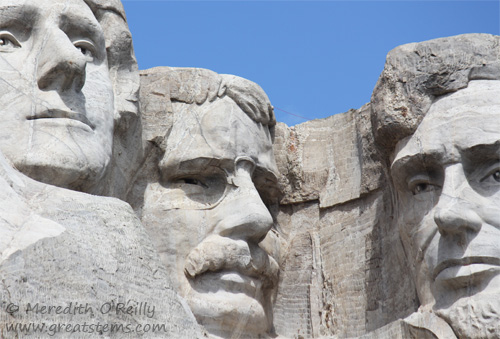

The carving depicts four of the United States’ most important historical figures and Presidents: George Washington, Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt, and Abraham Lincoln. In creating his design, Borglum made multiple models of the four Presidents, and he used these as guides for the mountain sculpture. Construction officially began in 1927.

Most of the sculpting work was done with the skilled use of explosives. The finer details were created and smoothed out with pneumatic drills, chisels, and pneumatic hammers. The work was dangerous, men dangling off the cliff for hours each day, but no one died during the project (however, the breathing of granite dust did cause lung damage for some workers).

Each face is 60 feet tall, and each nose is 20-21 feet long. The mouths are 18 feet wide, and the eyes are 11 feet wide.

Throughout the process, Borglum carefully studied the light and progress from all angles, and he made changes accordingly to make use of shadow and rock to create the facial features. His careful guidance and use of a pointer tool on both the models and the giant carvings helped workers follow his instructions and precise measurements exactly.

The faces were completed by 1939. But the original plan had been to show the the Presidents’ torsos. When Gutzom Borglum died in 1941, his son Lincoln carried on the construction for a few more months, until lack of funding brought an end to the construction. Take a closer look at the four Presidents in the images above. You will see some of George Washington’s clothing, as well as the partial fist of Abraham Lincoln.

It’s interesting to note that there had been an attempt in 1935 to include feminist leader and suffragette Susan B. Anthony to the four figures of Mount Rushmore. However, Congress defeated this motion. I’d like to think that her face among the other historical figures would have been a powerful symbol of pride for American women, and perhaps some of the issues in today’s political arena — namely, women’s rights and equality for women — would be a given rather than a continuing battle.

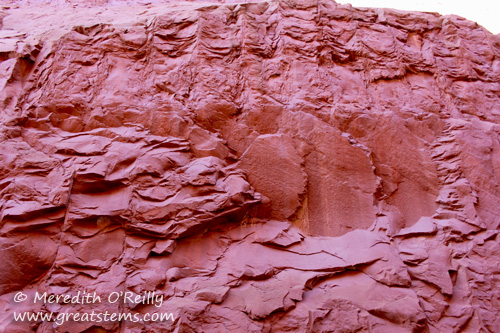

From Mount Rushmore, we headed next to Badlands National Park. Not really knowing what to expect, it was still what we expected, if that makes sense — striking geologic formations affected by years of erosion and deposition.

An ancient sea covered the area some 69 million years ago, and deposits of sediments began. After the sea retreated, more sediments were deposited with successive land environments. It wasn’t until about 500,000 years ago that erosion became a major factor in the shaping of the land, and erosion continues to change the area.

Though the Badlands’ deep canyons and buttes at first appear harsh and desolate, there is life all around. Much of the park is mixed-grass prairie and home to all sorts of wildlife, including prairie dogs and badgers, birds and bison, bighorn sheep and bobcats, insects and reptiles, and more.

Though the only mammals we saw personally during our Badlands visit were small chipmunks, we did see many birds, including this Black-billed Magpie.

While it’s hard to fall in love with the Badlands, their rugged beauty cannot be denied, especially when the sunlight and/or rain shows their beautiful coloration.

At last it was time to head home to Texas. Along the way, we stayed overnight at our friends Cynthia and Pat’s farm in Kansas.

Beautiful and buzzing with hummingbirds — of course I was delighted! We enjoyed a wonderful visit, delicious food, and great company. A big thank you to our hosts!

Of course a farm isn’t complete without bunnies, not that farmers would agree with that statement.

But I didn’t mind the quiet moments I spent with this rabbit, who contentedly posed for the camera while enjoying a bit of grass.

What a year of traveling this has been! With our Everglades trip in March, then our summer trip to Utah, Wyoming, and South Dakota, we have traveled many thousands of miles and covered a big chunk of the United States! The varying beauty of this great land and all its rich history, the positive and the negative, are opening my boys’ eyes globally, giving them a sense of both who they are in this world and a better understanding and appreciation of the world they should value and protect. If you’ve thought about making similar trips on your own or with your family, I encourage you to do so as soon as you can!

Thanks for journeying with us — M

Yellowstone is home to some 10,000 hydrothermal features. Aside from hundreds of geysers, the national park also has hot springs, mudpots, and fumaroles, or steam vents. These first images show one of my favorite hot spots, so to speak — Grand Prismatic Spring.

Yellowstone is home to some 10,000 hydrothermal features. Aside from hundreds of geysers, the national park also has hot springs, mudpots, and fumaroles, or steam vents. These first images show one of my favorite hot spots, so to speak — Grand Prismatic Spring.

However, I will say that my pants earned their very own Yellowstone patch.

However, I will say that my pants earned their very own Yellowstone patch.

We did have great luck to be near the Beehive geyser just as it was getting ready to erupt. First, the indicator vent let loose, prompting folks to gather around for the big event to come. Some of them pulled out rain ponchos, too — clearly they knew something….

We did have great luck to be near the Beehive geyser just as it was getting ready to erupt. First, the indicator vent let loose, prompting folks to gather around for the big event to come. Some of them pulled out rain ponchos, too — clearly they knew something…. A few minutes later, Beehive let loose in a thrilling display. Its powerful water column can reach heights up to 200 feet. Because it is close to the boardwalk, water droplets will sometimes drench the crowds in temporary rain, which fortunately is remarkably cool by the time it comes down. Again, we had luck — the wind shifted to our left just as Beehive erupted, soaking other visitors but not us and most importantly not our cameras. And by the way, I really do mean soaking for those other poor folks.

A few minutes later, Beehive let loose in a thrilling display. Its powerful water column can reach heights up to 200 feet. Because it is close to the boardwalk, water droplets will sometimes drench the crowds in temporary rain, which fortunately is remarkably cool by the time it comes down. Again, we had luck — the wind shifted to our left just as Beehive erupted, soaking other visitors but not us and most importantly not our cameras. And by the way, I really do mean soaking for those other poor folks. Another lucky moment for us was being on hand for the eruption of the grand geyser that is cleverly known as Grand Geyser. It also can reach 200 feet, and its display is as impressive as its name implies.

Another lucky moment for us was being on hand for the eruption of the grand geyser that is cleverly known as Grand Geyser. It also can reach 200 feet, and its display is as impressive as its name implies. The walking trail takes you past numerous other hydrothermal features, some with impressive sinter formations. Siliceous sinter comes from deposits of silica dissolved by hot water passing through rock called rhyolite. Above, you can see a thin sinter crust around Heart Spring. The deep blue color of the hot spring indicates that this water is super hot, so hot that even Yellowstone’s heat-loving algae and bacteria can’t survive.

The walking trail takes you past numerous other hydrothermal features, some with impressive sinter formations. Siliceous sinter comes from deposits of silica dissolved by hot water passing through rock called rhyolite. Above, you can see a thin sinter crust around Heart Spring. The deep blue color of the hot spring indicates that this water is super hot, so hot that even Yellowstone’s heat-loving algae and bacteria can’t survive.

The West Thumb Geyser Basin, by the way, overlooks the large, blue Yellowstone Lake, and many hydrothermal features can be found right along the edge of the lake, as well as IN the lake.

The West Thumb Geyser Basin, by the way, overlooks the large, blue Yellowstone Lake, and many hydrothermal features can be found right along the edge of the lake, as well as IN the lake. Why do all these hydrothermal features exist at Yellowstone? Simply stated, Yellowstone is on top of a large volcano. This supervolcano erupted 2.1 million, 1.3 million, and 640,000 years ago, forming three overlapping calderas, or geographic depressions. The last major eruption formed the Yellowstone caldera that would one day become the bulk of park we know and love. The Yellowstone caldera sits on top a giant hotspot. Magma flows as close as 2-5 miles below the surface, releasing tremendous heat. Water from snow and rain fills the underground plumbing and gets heated, sometimes to super temperatures of 400 degrees Fahrenheit when pressurized. It is this heating of water, combined with many small earthquakes and other natural processes affecting underground channels, that give Yellowstone its dynamic, impressive, and quite numerous hydrothermal features. The above photo shows that some of these changes can occur in the most unexpected places.

Why do all these hydrothermal features exist at Yellowstone? Simply stated, Yellowstone is on top of a large volcano. This supervolcano erupted 2.1 million, 1.3 million, and 640,000 years ago, forming three overlapping calderas, or geographic depressions. The last major eruption formed the Yellowstone caldera that would one day become the bulk of park we know and love. The Yellowstone caldera sits on top a giant hotspot. Magma flows as close as 2-5 miles below the surface, releasing tremendous heat. Water from snow and rain fills the underground plumbing and gets heated, sometimes to super temperatures of 400 degrees Fahrenheit when pressurized. It is this heating of water, combined with many small earthquakes and other natural processes affecting underground channels, that give Yellowstone its dynamic, impressive, and quite numerous hydrothermal features. The above photo shows that some of these changes can occur in the most unexpected places.

Here, dissolved calcium carbonate from hot water rising through the limestone is deposited in the form of travertine.

Here, dissolved calcium carbonate from hot water rising through the limestone is deposited in the form of travertine.

But I found some of the prettiest artistry when I looked down for a closer look, where thermophiles and mineral deposits create tapestries of colors and shapes.

But I found some of the prettiest artistry when I looked down for a closer look, where thermophiles and mineral deposits create tapestries of colors and shapes.

How do plants and wildlife thrive around all these intensely hot, alkaline or acidic, and ever-volatile features? Well, many birds like the young Killdeer above enjoy flies that feast upon thermophilic bacteria at the edge of hot springs. This Killdeer walks along brown thermophilic mats, which indicates the temperature is around 90-100 degrees Fahrenheit. Hot yes, but okay for a bird to walk along.

How do plants and wildlife thrive around all these intensely hot, alkaline or acidic, and ever-volatile features? Well, many birds like the young Killdeer above enjoy flies that feast upon thermophilic bacteria at the edge of hot springs. This Killdeer walks along brown thermophilic mats, which indicates the temperature is around 90-100 degrees Fahrenheit. Hot yes, but okay for a bird to walk along. This American bison had us worried when we saw it laying down on Geyser Hill near Old Faithful, but it was still breathing — we checked (from afar). It turns out he’s an older Bison, and perhaps the warm geyser area made a good sleeping spot. He got up and wandered away after a few minutes. But quite often we would spot Bison scat and other droppings in hydrothermal areas. It’s important to recognize that there is still danger here — a Bison or Elk walking too close to the fragile crust near a geyser or hot spring could suffer a traumatic death.

This American bison had us worried when we saw it laying down on Geyser Hill near Old Faithful, but it was still breathing — we checked (from afar). It turns out he’s an older Bison, and perhaps the warm geyser area made a good sleeping spot. He got up and wandered away after a few minutes. But quite often we would spot Bison scat and other droppings in hydrothermal areas. It’s important to recognize that there is still danger here — a Bison or Elk walking too close to the fragile crust near a geyser or hot spring could suffer a traumatic death. Many plants thrive despite their warm-water surroundings. The Bison scat mentioned above actually has great effects on the landscape surrounding hydrothermal areas. The seed- and nutrient-rich droppings of Bison and Elk allow grasses to grow where once there was none.

Many plants thrive despite their warm-water surroundings. The Bison scat mentioned above actually has great effects on the landscape surrounding hydrothermal areas. The seed- and nutrient-rich droppings of Bison and Elk allow grasses to grow where once there was none. But other plants succumb to the effects created by the presence of heat, silica, or pH. A change in hot water flow can suddenly kill off old-growth pines. Geysers spray silica-rich waters, which can flow around nearby pine trees. This will eventually kill the trees because they will effectively drink up this water, drawing silica into their roots and trunks, which will harden over time until the plants die. But where some plants no longer live, other areas will support new growth. Nature continues.

But other plants succumb to the effects created by the presence of heat, silica, or pH. A change in hot water flow can suddenly kill off old-growth pines. Geysers spray silica-rich waters, which can flow around nearby pine trees. This will eventually kill the trees because they will effectively drink up this water, drawing silica into their roots and trunks, which will harden over time until the plants die. But where some plants no longer live, other areas will support new growth. Nature continues.

Even so, we redid this photo several times, because Logan’s head kept blocking out the Grand Teton (not that we were surprised). We finally got one showing Grand Teton, but then Nolan’s head got cut out of the picture. Alas.

Even so, we redid this photo several times, because Logan’s head kept blocking out the Grand Teton (not that we were surprised). We finally got one showing Grand Teton, but then Nolan’s head got cut out of the picture. Alas.

Grand Teton National Park in summer still has many beautiful wildflowers, such as Indian Paintbrush.

Grand Teton National Park in summer still has many beautiful wildflowers, such as Indian Paintbrush.

We just returned from our 2012 summer vacation, in which the boys and I left Austin and headed west to Utah, north to Grand Teton and Yellowstone (where Michael joined us via airplane), east to the Badlands, south to our friends’ farm in Kansas, and then all the way home again. It was our longest road trip to date. Combine that with our trip to the Everglades in the spring, and we have really managed to tour a big chunk of the United States in this year alone!

We just returned from our 2012 summer vacation, in which the boys and I left Austin and headed west to Utah, north to Grand Teton and Yellowstone (where Michael joined us via airplane), east to the Badlands, south to our friends’ farm in Kansas, and then all the way home again. It was our longest road trip to date. Combine that with our trip to the Everglades in the spring, and we have really managed to tour a big chunk of the United States in this year alone!

But we were just as enthralled with the many skinks and other lizards we saw as we walked along the trails. In fact, we got a little competitive about it, seeing who could find the most lizards, some worth two points if they were less common than others. Snakes were worth 15 points, but alas we didn’t find any.

But we were just as enthralled with the many skinks and other lizards we saw as we walked along the trails. In fact, we got a little competitive about it, seeing who could find the most lizards, some worth two points if they were less common than others. Snakes were worth 15 points, but alas we didn’t find any.

it opens out to a much bigger and colorful scene, where the trail continues.

it opens out to a much bigger and colorful scene, where the trail continues.